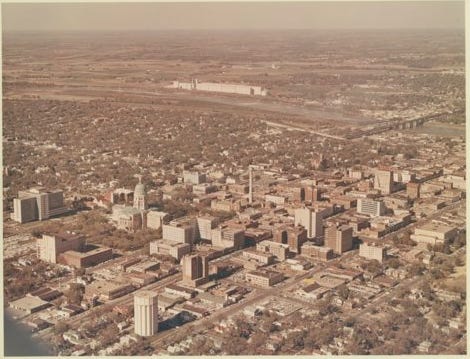

Topeka, Kansas, 1966

This morning I closed a contribution to a forum in the next issue of The Drift. The editors asked me if autofiction is over and whether the pandemic killed it. You can read my remarks when the issue comes out, but it reminded me of the piece below, which ran in the Fall 2019 issue of Sewanee Review. I doubt either that autofiction or novels reflecting on the Trump administration are going to stop being written anytime soon, but this book might have represented both their peak and their conjuncture.

HOMO TRUMPIENS:

BEN LERNER’S THE TOPEKA SCHOOL

It’s tempting when considering the last thirty years of American fiction to adopt the speculative framework proposed by David Foster Wallace in his 1993 essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” and extend it to the present. The dominant mode among the young writers of his generation—Bret Easton Ellis, Mark Leyner, and A. M. Homes, among others: what some were then calling “post-postmodernism”—was in his view flat, numb, cynical, saturated in pop imagery, an analog to the “televisual attitude,” a form of rebellion against structures of authority whose meanings it had tired of even bothering to examine. The style was a sign of exhaustion, fiction devolved to mere stand-up comedy in prose. Wallace predicted the next rebels would be “anti-rebels” who endorsed “single-entendre values” instead of irony, self-consciousness, and fatigue. They would treat “old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction.” They would be sincere.

The sincere turn did arrive, though not exactly as Wallace predicted. It didn’t do away with cynicism so much as set it up as an ogre to be defeated, as in the dystopian rescue narratives of George Saunders’s stories. It didn’t do away with pop imagery so much as valorize it, as in the superhero bildungsromans of Jonathan Lethem and Michael Chabon. And it didn’t conjure new sources of reverence so much as locate them in the tragedies of the past and then sentimentalize them, as in the third-generation Holocaust narratives of Jonathan Safran Foer and Nicole Krauss (and again Chabon). If authority was still suspect under George W. Bush, at least the end of history was over, and a sense of American innocence had been regained after 9/11, the attacks that launched a thousand novels.

But if sincerity had to be buttressed by surrealism, superheroes, ahistorical improvisations, and artificial innocence, how sincere was it really? Soon enough there was Obama, who represented a restoration of the sort of authority American writers could revere, perhaps even identify with. There followed a turn to the authentic. Various strategies emerged among novelists, but none has drawn the critical heat directed at autofiction—a term that originated in French in the 1970s and in English has been applied largely to what the Germans call Künstlerromans, “artist’s novels” that dramatize the author’s formation and inscribe the creation of the novel on the book itself. Writers like Sheila Heti (a Canadian), Tao Lin, Jenny Offill, Teju Cole, and Elif Batuman have drawn on energies that had veered into the memoir, taken recourse to the diaristic and the essayistic, and deployed alter egos easily blurred with their authors. None of these strategies are exactly new, but they represent a departure from the dominant strain of realism, if not a drastic one.