MAILER TIME

Misunderstood and unjustly loathed

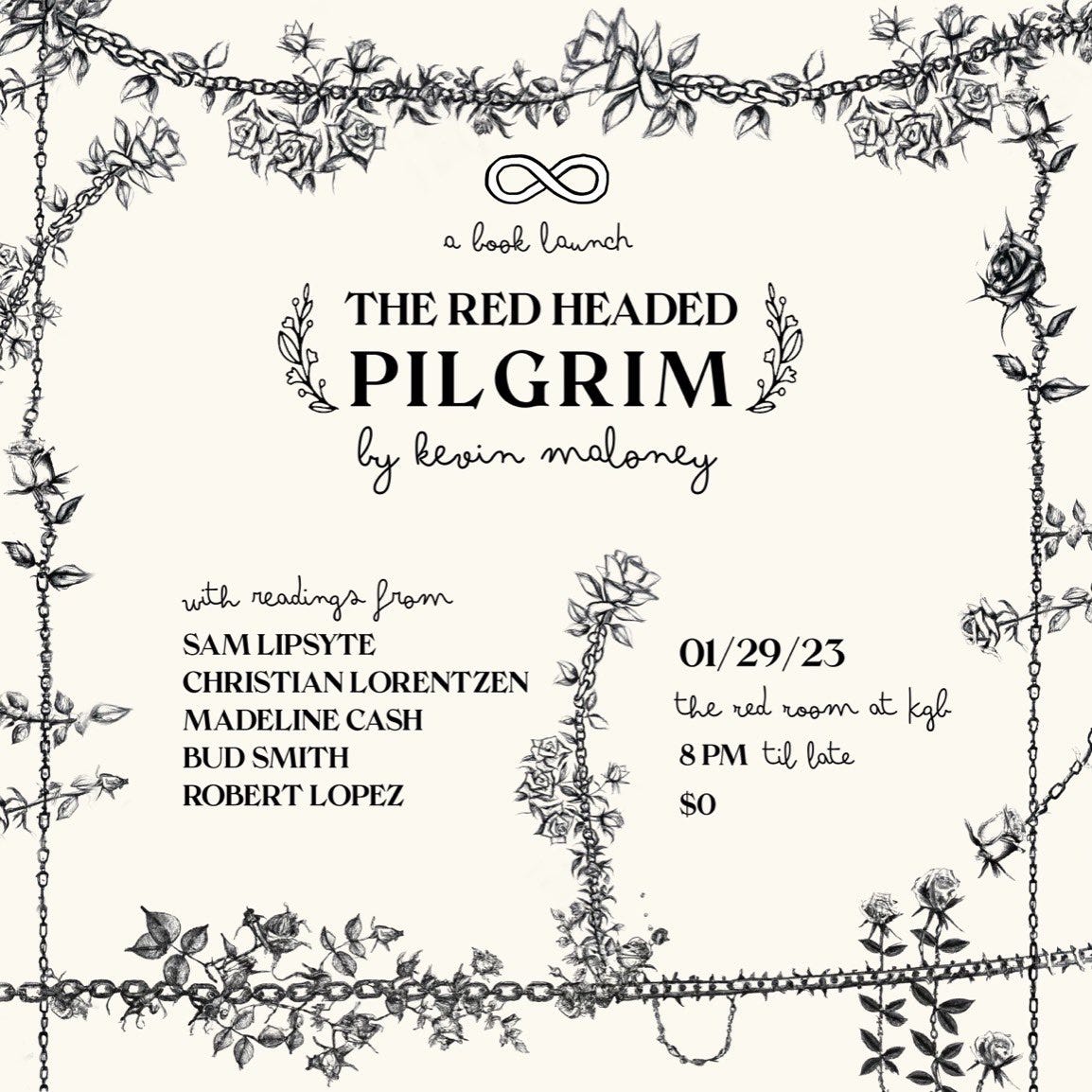

I am appearing in public three times in the next week. There are shows of Dimes Square on Tuesday and Thursday. The Thursday show is sold out, but tickets for Tuesday can be found here. You can avail yourself of the code "student" for a 75% discount (only for people actually in school) or the code “Tuesday” for 25% off (limited to 10 uses total) or the code “wealthcommon,” for the friends of Lorentzen discount. On Sunday night I will be reading at the launch of Kevin Maloney’s The Red-Headed Pilgrim, with Maloney, Sam Lipsyte, Madeline Cash, Bud Smith, and Robert Lopez.

Below, an old piece from my Bookforum archive on Norman Mailer.

The Gospel According to Norman

NORMAN MAILER: A DOUBLE LIFE BY J. MICHAEL LENNON. SIMON & SCHUSTER. HARDCOVER, 960 PAGES. $40.

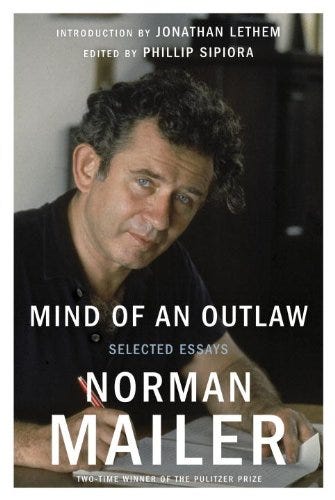

MIND OF AN OUTLAW: SELECTED ESSAYS BY NORMAN MAILER. EDITED BY PHILLIP SIPIORA, JONATHAN LETHEM. RANDOM HOUSE. HARDCOVER, 656 PAGES. $40.

In July at the Manchester International Festival, I saw a preview of Matthew Barney’s seven-part film opera River of Fundament. Barney explained that Norman Mailer, before he died, challenged him to adapt his 1983 novel Ancient Evenings, which he felt to be his most misunderstood and unjustly loathed work (“a muddle of incest and strange oaths,” James Wolcott wrote in Harper’s, “reducing everything to lewd, godly bestial grunts”). Barney admitted that it was a book he both loved and hated. In 1999 Mailer had acted in Barney’s Cremaster 2 as Harry Houdini, by family legend the grandfather of Gary Gilmore, the double murderer and subject of The Executioner’s Song (1979), Mailer’s last great success. Among the scenes Barney showed in Manchester were a staged wake for Mailer, filmed in the author’s Brooklyn apartment, attended by Paul Giamatti, whose head and feet are massaged by ghastly spirits, and presided over by Elaine Stritch; the melting down of a 1967 Chrysler Imperial—representing Osiris—at a Detroit steel mill shot to the accompaniment of a brassy orchestra performing in the rain; and a soliloquy delivered by Maggie Gyllenhaal as two slimy ghouls stimulate each other’s posterior apertures (to use Mailer’s preferred phrase). Here was the appropriately bizarre second coming of Norman Mailer: celebrity laden, anally fixated, overlong (it’s said that the film will be five hours in full when it premieres in February at the Brooklyn Academy of Music), and very expensive (the Detroit performance alone had a budget of $5 million).

Neither Matthew Barney nor Cremaster 2 are mentioned in J. Michael Lennon’s new biography Norman Mailer: A Double Life; the year 1999 is mentioned only in reference to the author’s wife Norris’s hysterectomy. By then, nearly two decades had passed since the Pulitzer Prize had gone to The Executioner’s Song, and it seemed that the culture had come down with a terminal case of Mailer fatigue. He still made the best-seller lists, and he had garnered some positive reviews for his past three books (biographies of Lee Harvey Oswald and Picasso and a novel about Jesus Christ), but there was little sign that the rising generation admired him. “Unutterably repulsive,” David Foster Wallace wrote in a letter as he was reading The Armies of the Night. “I guess part of his whole charm is his knack for arousing strong reactions.Hitler had the same gift.” Mailer was among “the Great Male Narcissists” of postwar American fiction, Wallace wrote in 1997, “now in their senescence.” Yet Wallace practiced the sort of subjective, novelistic, personality-saturated journalism that would scarcely have been possible without the example of the New Journalists of the 1960s, Mailer foremost among them. By the time he went on the campaign trail with John McCain in 2000, Wallace was referring to himself in the third person (as ROLLING STONE), Mailer’s signature move. Wallace too, with his footnotes and the great effort he put into suppressing his narcissism, aroused strong reactions.