I was writing down memories of Lewis Lapham, one of my heroes and one of my first bosses in the magazine game, on Thursday when the Washington Post called and asked me to write an essay:

In an age of hyperbole and literal-mindedness, Lewis H. Lapham, who died last week at the age of 89, was a master of ironic understatement. As the personal computer and the touchscreen turned everyone into a prose minimalist, he remained committed to a mandarin style, the majority of his sentences demonstrating the force of periodicity and sinuosity. Rare among intellectuals, he was hardly ever not funny, even on the most serious of subjects. “Funny” is not a word I recall him ever using in print, but wherever he was, laughter followed. Unlike his peers in the era of New Journalism, with whom he was sometimes grouped, he never endeavored to make himself the main character, though his readers could always sense that they were in the presence of a strong and reliable narrator with a singular talent for metaphor. These were his qualities as a newspaperman, magazine feature writer and monthly columnist. He was also one of the great editors of his time, reshaping America’s oldest monthly, Harper’s Magazine, and creating Lapham’s Quarterly from scratch.

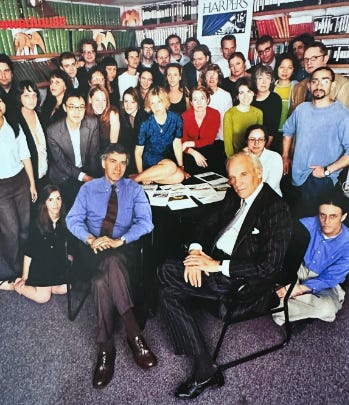

Lucky for me that I got to work for him. I was an intern at Harper’s in the spring of 2002. One morning, Lapham ran out of Parliaments while trying to finish his column, and I bummed him a couple, to be repaid the next week with a pair of Cuban cigars. One afternoon in the office conference room we watched in disbelief as Secretary of State Colin Powell presented the case for the invasion of Iraq based on satellite photos of aluminum tubes that were said to somehow indicate the preparation of nuclear warheads or at least the vaguer “weapons of mass destruction.” One night a few weeks later we watched the flashes on the screen as the first bombs were dropped on Baghdad. Lapham was one of the few voices in national publications who strongly opposed the war. Later he called for the impeachment of George W. Bush. These stances, lonely at the time, have been vindicated in the tumultuous decades that have followed. Lapham, however, was never a pundit. As columnists more and more fashioned themselves as outside electoral strategists for one party or another, he kept up the tradition of the observer as Socratic gadfly. He believed in America as a republic, at its best a democracy, but never as an empire. He was a skeptic of power but never a cynic when it came to human beings.

The rest is here.

I spent Thursday night returning to Lapham’s writings in Harper’s, selections collected here. Along with his Paris Review interview, I recommend a long spell with his prose.