NEW BEDFORD, MASS.—It is better to write about the past than the future. There is a record of the past and the future is unknowable. I was wrong when I ventured into predictions about the presidential election last fall, wrong about Trump as a “spent force,” and perhaps wrong about the utility of the “fascism thesis,” though that might be a case of the Republicans deciding that if the shoe fits they might as well try it on. I misunderstood the political moment, and didn’t see the events of the last few months coming, even though I had witnessed enough to convince me that the Democrats’ campaign of joy would be a bloodless failure in a bloody world they had made bloodier. I might have predicted the continuing descent of literary discourse that’s occurred over the last few months (TOPIC A: Are books for boys or are books for girls? TOPIC B: Do moms and dads make the best writers or what? TOPIC C: Show us your bank statement, please.) but that’s an easy one, if also dispiriting.

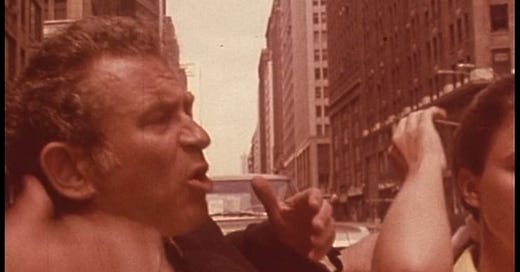

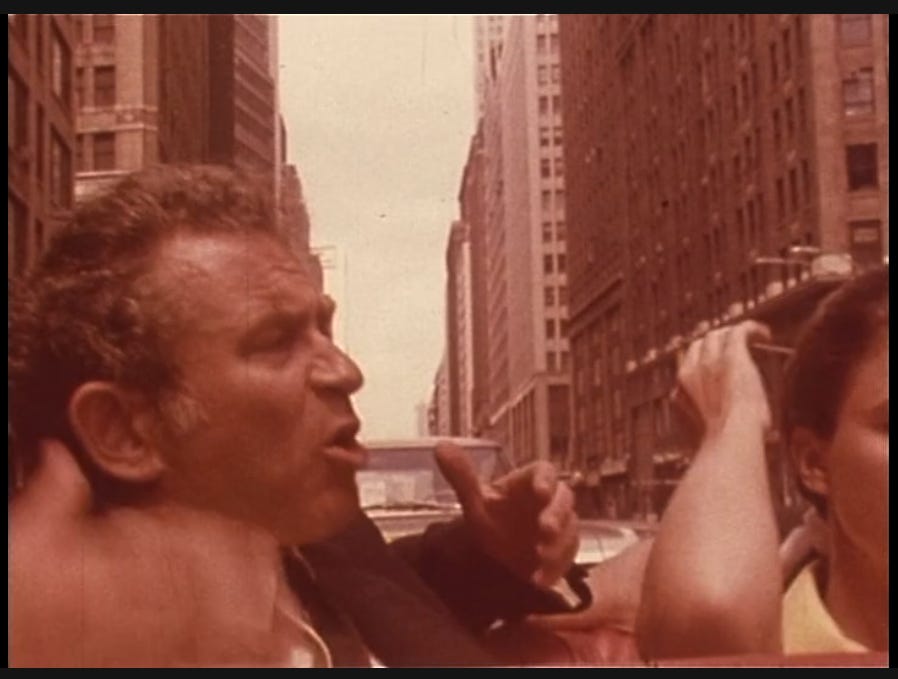

I had somehow never seen Norman Mailer vs. Fun City, Dick Fontaine’s documentary about Mailer and Jimmy Breslin’s 1969 Democratic primary campaign for mayor and City Council president, until last month. “The average citizen of New York,” Mailer says in the opening frames, shots of driving through a tunnel (perhaps the Battery Tunnel?—a billboard for Dewar’s appears above the entrance, not one I recognize), “thinks upon the administration of his city with horror. He thinks with horror upon the idiocy of attempting to change anything in the city because he knows he will be reduced to impotency and defeat. We cannot look for political solutions anymore. We must look for historical solutions.” It’s tempting to assert that this sounds like the rhetoric of certain political insurgents of recent memory, but Mailer resembled Trump only in the size of their egos. His self-declared “left conservative” platform had more in common with the politics of Bernie Sanders, though it strayed further into the unlikely, the impractical, the preposterous. Mailer’s emphases—on local self-government, pollution reduction, and restraining the technological society—were similarly humane. “I’m not running as a leftist,” Mailer says. “I’m running to give power to the people because without it you have nothing.” He speculates that the next war will be between those who have bulldozers and those who don’t.