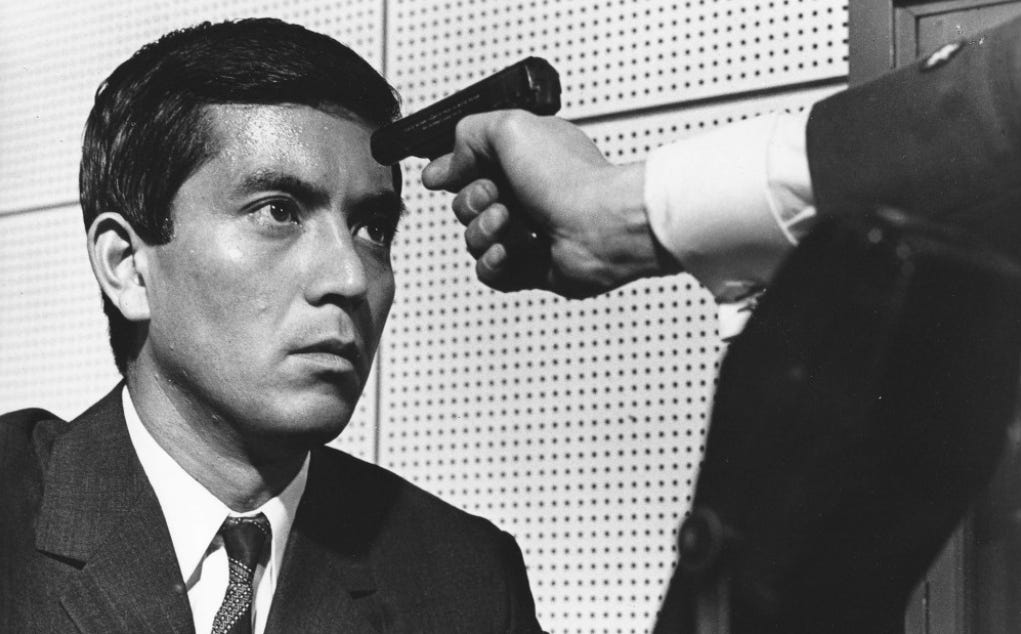

A gun to the radio presenter’s head.

A note to subscribers: Sorry for the delay between posts. I’ve been working on a long piece for a magazine, and it’s taken me more time than expected. Below are remarks on a film I saw the other night at FilmForum, Japan’s Longest Day (1967), directed by Kihachi Okamoto. Coming soon are Part II of my essay on Jean-Patrick Manchette’s novels, a reading of the late Mark Lanegan’s memoir, and a review of Chuck Klosterman’s The Nineties. An audio recording of my Montez Press Radio show, Truth & Beauty, co-hosted by Caroline Debnam, will also be sent out; the first episode is an interview with Matthieu Aikins, author of The Naked Don’t Fear the Water, and Gary Indiana, whose essay collection Fire Season will be published in April. Again, I apologize for the delay, and thank you for subscribing. Japan’s Longest Day is showing again at FilmForum on Friday March 4 at 12:40 pm.

Deliberating on surrender.

I don’t know exactly how long it takes for the first head to roll in Japan’s Longest Day, but it feels like a long time, probably 70 or 80 minutes. The head literally rolls, having been severed from its body, that of an officer of the Imperial Guard, by a blow from a rebel’s sword. The rebels are plotting a coup to prevent the Emperor from surrendering, and they shoot their commander dead because he won’t go along with them. The rest of the film is a litany of violence.

The film’s opening includes footage of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and their aftermaths, some of the images of suffering gruesome enough to make you turn your eyes away from the screen. There follows a series of meetings. There are meetings of government ministers. There are meetings of Army officers. When the war minister, played by Toshiro Mifune, delivers the news of the Emperor’s decision to accept the conditions of the Allies’ Potsdam Declaration to his subordinates many of them break out in tears or simply moan, knee-jerk reactions of humiliation and dishonor. Some of the moans are high-pitched squeals. It’s hard to tell whether they’re restraining themselves and can’t help expressing these emotions or are making a show of restraining themselves and moaning anyway to make a show of expressing their shame and sorrow. (Many of them know they will kill themselves.)

Needless to say those aren’t the only emotions on hand. Anger, truly psychotic anger, is the other. The imperial guard officers plotting the coup are out of their minds. So is the leader of a battalion marching on Tokyo. He is emaciated and his teeth look like little tombstones. He screams: ‘The war must continue!’ He’s not the only one who says this line. His troops are shoeless and march with bandages around their feet. The plot of the film concerns their efforts to prevent the Emperor from surrendering, by taking his palace, which the get but not him, and assassinating the prime minister, whose house they machine gun (he’s fled to the suburbs). They learn that the Emperor, whose voice we hear but whose face we never see, has recorded his surrender speech on a vinyl record and that it will be played over the radio the next day at noon. They take the radio station. The station manager is unflappable, as is the Emperor’s chamberlain. They are the film’s only characters who stay cool and seem happy that the war is ending.

The war minister.

Mifune’s war minister knows that the end of the war is right but he also knows that he must commit seppuku. The other films I can think of that include such ritual suicide are Paul Schrader’s Mishima and Kurosawa’s Rashomon (also starring Mifune). Like much of the violence in Japan’s Longest Day, the seppuku scene’s special effects are very B-movie, and all the more brutal for it. Okamoto lingers on the war minister’s preparations cutting away to other parts of the night’s action after each move he makes, unfolding a cloth or unsheathing a dagger, on the way to slicing open his belly and opening a vein in his neck. Before kneeling down to die, he makes the rounds and says goodbye to ministers and officers, bearing gifts, a box of cigars in one case, and saying nothing of his intentions though they know what he’ll do. When told of the coup plot in progress, he dismisses it and says it will never succeed because the Eastern Army won’t join it. He’s right.

Plotters of the failed coup.

The plotters never get the record. The friend I saw the film with knows her Japanese history, which I don’t and said she recalled that the true story of the events of August 14 and and 15, 1945, might have involved a decoy record. I’m not interested much in the details and their accuracy. The movie is about the psychotic logic of war, how it perpetuates itself, and warps the minds of its combatants and their civilian leaders. It is riveting and frightening, a good movie to watch this week.

The war minister takes his own life.